Arts Media Outlets of the Civil Rights Movement Pdf

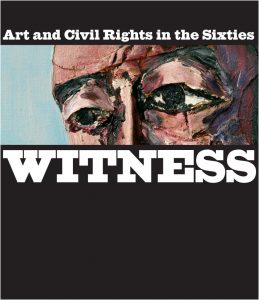

Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties

Teresa A. Carbone and Kellie Jones

With Connie H. Choi, Dalila Scruggs, and Cynthia A. Young

Brooklyn Museum, 2014; 170 pp.; $40.00; ISBN 978-1580933902

This by July marked the one-half-centennial ceremony of Freedom Summer and the passage of The Ceremonious Rights Act of 1964. The Human action – amended a decade after Brown v. Board of Education – banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sexual practice, or national origin, and demanded that all peoples have equal access to voter registration, employment, and public facilities. Many folks observed the anniversary by organizing programs, giving speeches, and writing op-eds that celebrated Lyndon B. Johnson'due south signature legislation and the equality information technology supposedly mandated. Critical commentators soberly noted the renewed Republican assault on voting rights, and pointed out that segregation remains a defining characteristic of the criminal justice arrangement, schools, and workplaces across the nation.

This by July marked the one-half-centennial ceremony of Freedom Summer and the passage of The Ceremonious Rights Act of 1964. The Human action – amended a decade after Brown v. Board of Education – banned discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sexual practice, or national origin, and demanded that all peoples have equal access to voter registration, employment, and public facilities. Many folks observed the anniversary by organizing programs, giving speeches, and writing op-eds that celebrated Lyndon B. Johnson'due south signature legislation and the equality information technology supposedly mandated. Critical commentators soberly noted the renewed Republican assault on voting rights, and pointed out that segregation remains a defining characteristic of the criminal justice arrangement, schools, and workplaces across the nation.

An exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum entitled Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties takes a markedly different approach to the anniversary. Co-curated by Teresa A. Carbone, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of American Art at the Brooklyn Museum, and Kellie Jones, Associate Professor of Art and Archaeology at Columbia University, the evidence focuses on the intersection of art and activism to deliver a complex portrait of the Civil Rights Move as a movement of millions rather than the piece of work of a few highly visible leaders. By bringing together works in a diverse range of media, styles, and genres, Witness fashions a polyvalent narrative that problematizes the historicist circumscription of the Civil Rights Movement to an easily delimited menstruation. Rather than glorify big names winning large gains on the progressive political forepart of a racial equality we can call our own, the show reveals a critical focus on the Movement as many interconnected movements informed past an insurgent aesthetic vision whose urgent phone call for justice must even so exist met. Witness narrates the Civil Rights Movement from the perspective of the artists and image-makers who were called to participate in it, and reveals a stunningly capacious aesthetic battleground whose relationship to 1960s freedom struggles has been persistently downplayed past fine art historians.

At the Brooklyn Museum, viewers were greeted by two paintings upon entering the exhibition space: May Stevens's Award Curl (1963) and Benny Andrews's Witness (1968). Both paintings speak to the grassroots cadre of the Move. Stevens' subjects are the student activists who put their bodies on the line to integrate education; Honor Roll displays their rough-hewn names as if the students had themselves scrawled them upon a collective scroll earlier dipping off into the uncertain morass of southern life and an unequalled education in their country's political chicanery. Andrews's Witness, meanwhile, affirms the stolid grace of the sharecroppers of the Black Belt – in this case, southwest Georgia – who lived under the oppressive thumbs of debt, hunger, and land-supported violence and who greeted the formidable call of freedom with knowing resolve and an open spirit. This focus on a multitudinous grassroots connected throughout the exhibit, with artworks bundled thematically rather than chronologically under the banners "Black Is Cute," "Politicizing Pop," "Presenting Evidence," "Integrate/Educate," "American Nightmare," "Sisterhood," "Global Liberation," and "Beloved Customs." This curatorial decision immune pieces equally stylistically various as Yoko Ono's Voice Piece for Soprano (1961) and Edward Kienholz's It Takes 2 to Integrate (Cha Cha Cha) (1961) to occupy the same space in a dissonant resonance that recasts many major international artworks of the mid-century within a ceremonious rights framework.

The curators' decision to emphasize the grassroots core of 1960s freedom struggles while elucidating the revolutionary currents within that period's visual civilization takes center phase in the exhibition catalogue. Witness is comprised of essays written by the exhibition's curators, along with pieces past Connie H. Choi and Cynthia A. Young and a thorough chronology of the Civil Rights Movement composed by Dalila Scruggs. The essays, entitled "Ceremonious/RIGHTS/ACT," "Documentary Activism: Photography and the Ceremonious Rights Movement," "Exhibit A: Evidence and the Art Object," and "Civil Rights and the Rise of a New Cultural Imagination" requite critical heft to the exhibition's focus on the artist as activist. They also provide a revisionary portrait of aesthetic modernism from an Afrocentric perspective that defies the modernist adage that artists in the mid twentieth century were primarily concerned with medium specificity and material expression (44). Andrews's Witness names the show and adorns the comprehend of the exhibition catalogue to remind us of the cardinal importance that bearing witness had in shaping the political events of the 1960s – of the principal influence of representation on black peoples' textile and spiritual well-existence, and of the massive part that visual culture played in the buildup of Ceremonious Rights struggles.

In the book's keynote essay, "CIVIL/RIGHTS/ACT," Jones uses the concept of "total well-being" – equally cited in the constitution of the Earth Health System and adopted by the Blackness Panther Party as a right to which African Americans had been historically barred – as the defining intersection between art and ceremonious rights. Highlighting art's capacity to generate collective action, her essay begins with a discussion of the ways that artists similar Noah Purifoy and Lygia Clark engaged members of their communities in the quest for artistic bureau. Their makeshift exhibition settings, Jones points out, were spaces in which borough engagement could exist radically redefined. Jones borrows Leigh Raiford's phrase "insurgent visibility" to describe the means that artists and documentary photographers made visible black social and political power and identity apart from the hegemonic terms laid out by white supremacist visual culture (43). Virginia Jaramillo, Leon Polk Smith, and Charles Alston, for example, pushed abstraction to fresh political heights by working in a black and white palette that signaled the hard-edged battle to end segregation. Representational works, such as Elizabeth Catlett's Home to My Young Black Sisters (1968), Charles W. White'south Birmingham Totem (1964), and Ben Shahn'south Homo Relations Portfolio: Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner (1965) directly reference pivotal moments and figures from the period. Other artists, similar Barkley L. Hendricks and Emma Amos, operationalize the conceits of color field and pop fine art to face up the power and beauty of cocky-representation alongside the aching scrape of integration. Jae Jarrell's Urban Wall Suit (c. 1969) combines painting, graffiti, and mural aesthetics into a textile wonder. Other artists like Emory Douglas, Robert Indiana, Barbara Jones-Hogu, and Rupert Garcia are highlighted for their work in poster graphics and printmaking. Jones also notes the radically performative future inherent in geometric abstraction paintings past William T. Williams and Joe Overstreet, as well every bit in Tom Lloyd's electronic light sculpture, Narakon (1965). Overall, these artists' holistic concern with the wellness of the community situates the aesthetic mandate of the Civil Rights Movement within the Africanist representational politics of the New Negro move, with Romare Bearden'due south collages as the nearly hit instance. As Jones writes: "Activities in art and elsewhere insisted on the multiple viewpoint, and a earth where life, art, aesthetics, and culture were not contained by the singularity of a Western modernist signal of view" (44).

The other essays delve more deeply into the ways that documentary photography, color field, and collage were adopted as aesthetic strategies for combatting the abstract violence so frequently committed in popular visual depictions of African Americans and Civil Rights activists. White corporate media publications such as Look, Life, and Newsweek craved sensational images of violence and poverty. In "Documentary Activism: Photography and the Civil Rights Movement," Choi invokes Martin Berger'due south argument that these sensational images framed African Americans every bit passive victims and allowed whites to distance themselves from their complicity in structural forms of privilege and violence. Her essay focuses on the ways that documentary photographers dedicated themselves to the move, working for the Educatee Not-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Briefing (SCLC) to testify to the tedium, sweat, and violence that activists faced as they registered voters, occupied lunch counters, and marched in defiance of white supremacist law in the South. In improver to capturing the violence that activists faced (SNCC'southward Photograph Agency was tasked with keeping an eye on law), documentary photographers sought to command the epitome of the movement every bit grassroots and youth-led. In its inclusion of lesser-seen Civil Rights photographs such equally Charles Moore's Voter registration, 1963-64 and Roy DeCarava's muted, close-upward portraits of activists, Witness shows move participants equally individuals rather than as "symbolic components of a nameless multitude" (62). Choi offers a deft portrait of the Civil Rights lensman equally activist and historian, writing: "In turning their lenses to the crowd to document the whole of the movement, photographers reinforced their own sense of belonging to that company of supporters" (58).

In "Exhibit A: Bear witness and the Art Object," Carbone examines how artists worked with the idea of visual evidence quite differently than did the documentary photographers who struggled alongside them. Reared in the age of abstraction and trained to expect downwardly on social realist art and photography of the 1930s, immature artists in the 1960s were challenged to "show to the facts" of racial and economic injustice differently – as producers rather than mere recorders of reality (81). Afterwards forming in the late summer of 1963 at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the art collective Screw turned to abstraction in gild to interrogate the relationship betwixt race and the visual in their show "Black & White." In addition to employing black paint in abstract compositions that highlighted blackness's symbolic resonance, Screw members like Romare Bearden and Merton D. Simpson turned to collage as a way to mobilize imagery from the popular press within a polyvalent artful field that problematized the reductive portrayal of blacks in the white media. Carbone celebrates Bearden's collages for their ability to manipulate "photography's raw facts into a truer form of bear witness" by overlaying appropriated photographic images of blacks on top of each other to compose saturated, animated, and contradictory scenes (84). Betye Saar also took upwards the language of collage in assemblage works that infect the visual linguistic communication of photographic proof with the ambiguous ability of illustration, painting, found imagery, and sculpture. Works like Saar's Is Jim Crow Really Expressionless? (1972) combine photography with coins and other objects into a coffin-like altar to address the creative person's personal experience of beingness excluded from white galleries. Other assemblage works testify non-representationally to the turbulence of the fourth dimension through a tactile immediacy; Robert Rauschenberg'south Coexistence (1961) combines the damaged remnants of a police barricade with wire and oil paint, while Noah Purifoy's Watt's Riot (1966) and John T. Riddle Jr.'s Untitled (Fist) (1965) manner the traumatic refuse left backside in the wake of the Watts Rebellion into loving testimonies to black power.

In "Civil Rights and the Rise of a New Cultural Imagination," Young highlights the influence of African American women's activism in the S and anti-imperialist movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America on the U.South. Civil Rights Movement. In addition to discussing the role of the Women's Political Conclave in spearheading the Montgomery Autobus Cold-shoulder in 1955, Young underscores the extent to which Civil Rights heavyweights like Dr. King, Maya Angelou, Nina Simone, Richard Wright, and LeRoy Jones were shaped by Tertiary World Decolonization movements, particularly in Republic of ghana, Cuba, and China. Cuban moving-picture show and literary collectives, writes Young, sparked "a Pan-American revolution in the Arts, one that shifted the cultural centre of gravity for 1960s radicals from the United States to Cuba" (113). Young's transnational narrative of the Civil Rights Move is accompanied by illustrations of art works like LeRoy Clarke'southward At present (1970), Jae Jarrell's Ebony Family (c. 1968), and Barbara Jones-Hogu's Nation Fourth dimension (1970), which were influenced by the radical graphics and mural art of Latin America, every bit well as by an Afrocentric celebration of black beauty and nationhood.

Throughout the exhibition catalogue, the authors highlight the participatory practices, alternative spaces, and democratic display methods – posters, murals, sidewalk exhibitions, and style shows – that artists employed to protest major museums' exclusionary practices (43).

Scrugg's Ceremonious Rights chronology, though commencement in familiar territory with the Supreme Court ruling on Brown v. Board of Teaching, fashions a clever critique of an fine art world that was riven in the 1960s by racism. Her unconventional genealogy focuses on the intersection of the arts and struggles for civil rights in the U.S. with the Vietnam War, the escalating violence of apartheid Southward Africa, the Cold War, the Stonewall Rebellion, and the escalation of the American Indian Movement. Scrugg's chronology is particularly important in that it is the only slice in the catalogue that demonstrates the impact of Ceremonious Rights organizing on feminist consciousness in its inclusion of major dates in the second moving ridge of the U.Southward. Women'south Liberation Movement: the foundation of the National Arrangement for Women in 1966, and an action past New York Radical Women against the Miss America contest in Atlantic Metropolis in 1968.

As an exhibit, Witness enacts a reverent space for an aesthetic contemplation of the historicity, complication, and continuity of civil rights struggles. The exhibit'southward accompanying catalogue highlights the inextricable relationship betwixt art and politics by providing a complex portrait of artists' aesthetic strategies for combatting racial and economic injustice throughout the centre decades of the twentieth century. Witness expands our definitions of the Ceremonious Rights Movement, Modernism, and Black Arts past centering the visual every bit a cardinal battlefield for liberation and by highlighting an Afrocentric and internationalist modernism that is too ofttimes ignored by art historians.

Exhibition schedule: Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY, March 7-July six, 2014; Hood Museum at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., Fall 2014; Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin, Spring 2015.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1512

PDF: Gray: Witness

About the Author(south): Erin Gray is a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Source: https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/article/witness/